In the summer of 1131 AD, the armies of the Southern Song (南宋) and the Jin (金朝) were encamped on opposite sides of the Yangtze River (Changjiang 长江) and engaged in a pitched battle. General Liu Guangshi (刘光世) commanded the Southern Song army while General Wan Yanchang (完颜昌) led the forces of the Jin.

The two armies were of equal strength and neither side was able to advance on the other.

General Liu decided to try to break the stalemate through the use of an unusual instrument of propaganda.

He minted coins.

The coins were not meant to circulate as currency, however, because they were created to achieve the specific military goal of inciting defections among the enemy ranks.

The coins were made of bronze (copper), just like the common Chinese cash coins, but a few were made of silver and some of gold.

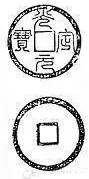

At the left is the image of one of the bronze coins. The inscription, written in regular script (kai shu 楷书), is read in a clockwise rotation as zhao na xin bao (招纳信宝).

The coin inscription zhao na xin bao (招纳信宝) is explained as follows. Zhao (招) means “to beckon” or “recruit”. Na (纳) translates as “to admit” or “to accept”. Xin (信) is a “letter”. Bao (宝) is a “treasure” which is the term that was used on Chinese cash coins (coins with a square hole in the middle) for two thousand years.

This rare coin is in the collection of the Hangzhou Museum (杭州博物馆). The coin was donated to the museum in 2006 by the family of Mr. Ma Dingxiang (马定祥) who was one of the most respected Chinese numismatists of the 20th century.

The coin has a diameter of 2.6 cm and a weight of 5 grams. One of the easily observed characteristics of these coins is that the bao (宝) character, at the left of the square hole, is unusually “tall”.

According to this article, the National Museum of China (中国国家博物馆) also has a bronze zhao na xin bao coin in its collection.

General Liu knew that many of the soldiers in the Jin army were ethnic Han Chinese (汉族), and not Jurchen (女真族), and that they had been forced to serve in the Jin military. He felt that many of these men were probably homesick and would like to escape and return to their homes.

General Liu implemented a new policy with the casting of the coins. When Jin soldiers were captured, instead of being killed, they were treated very well. The captured Jin soldiers were shown the newly minted coins and told that anyone carrying one of these special coins could return safely to their home. The captured Jin soldiers were then given the coins and told to return to the Jin army and give the coins to any of their compatriots who wished to desert and return home.

The soldiers returned to the Jin encampment and secretly distributed the coins to the other soldiers who wanted to leave.

The inscription zhao na xin bao (招纳信宝) therefore means it is a “treasure” or coin (bao 宝) that is “recruiting” (zhao 招) soldiers of the Jin who want to return home. They will be warmly “accepted” (na 纳) into the Song army encampment and the coin would serve as their “letter (xin 信) of introduction”.

Mr. Ding Fubao (丁福保) points out in his authoritative “Dictionary of Ancient [Chinese] Coins” (古钱大辞典) that zhao na (招纳) has the meaning of “submitting to the authority of another” (gui fu 归附). The inscription could therefore be interpreted to mean that the bearer of the coin can trust that he will be able to safely return to the authority of the Song.

Noted Chinese numismatists have proposed English translations of the coin inscription as “Trust Token for Recruits” and “Pass Coins“.

The reverse side of the coin, seen in the rubbings at the left, show the Chinese character shi (使) above the square hole. “Shi” (使) means “a messenger” or “envoy” which implies that the coin and bearer are on an official mission.

Below the square hole is a symbol that resembles the Chinese character shang (上) although it is reversed left to right and thus facing the wrong direction. The consensus of Chinese numismatists is that this is actually a “signature”, and possibly that of Liu (刘), although the exact translation has yet to be determined.

As mentioned above, some of these coins were also cast in silver and gold. Several Chinese coin references mention that in the past a few specimens of these coins were in the hands of private collectors. Unfortunately, the current location of these coins is unknown.

However, a Chinese reference (中华珍泉追踪录) provides some information regarding the silver version of the coin. During the Republican period (1912-1949), Mr. Fang Dishan (方地山) had a silver specimen in his collection. Mr. Yuan Hanyun (袁寒云) described this coin as being slightly larger than the bronze version. The shi (使) character above the square hole on the reverse side was slightly smaller. Most noteworthy, however, was that the character below the hole was not a “reverse” shang (上) like that on the bronze coin. The character resembled a 凵 (kan) with a 禾 (he) in the middle. This apparently was a signature but, again, the meaning is unclear.

Mr. Fang Dishan passed away in 1936 and it is not known what happened to his silver coin.

Regarding the gold version of the coin, the Baidu Encyclopedia reports that Mr. Chen Rentao (陈仁涛) owned a specimen. Mr. Chen passed away in 1968 and I have not been able to determine the whereabouts of this coin which is considered “priceless” and a “first-class cultural relic” (一级文物).

According to historical records, the coins achieved their goal as an instrument of psychological warfare. These coins guaranteeing freedom persuaded tens of thousands of Jin conscripts to defect to the Song. Some of the men decided not to return home but instead to join the fight on the side of the Song. The recruits were organized into two new armies, namely the “Red Hearts” (chi xin 赤心) and the “Army Appearing from Nowhere” (qi bing 奇兵). The flood of deserters, which included not only Han Chinese but also Jurchen and Khitan (契丹), was so great that General Wan and the Jin army were forced to retreat.

Because the coins were issued over a very short period of time and circulated in a very limited area, very few authentic specimens have survived.

These coins are quite rare and valuable. An authentic bronze zhao na xin bao coin would sell today for about 100,000 RMB ($14,500). As mentioned earlier, the silver and gold coins are so rare that they are essentially priceless.

Unfortunately, most of the zhao na xin bao coins seen today are fakes or reproductions.