Chinese Money Trees

Chinese legends speak of a

tree (yaoqianshu

摇钱树) that when shaken causes coins from its

branches to fall to the ground. Stories of these "money

trees" are even mentioned in such ancient Chinese historical

texts as the "Records of the Three Kingdoms" (san guo zhi 三国志) written

in the 3rd century AD.

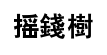

In numerous tombs in

southwest China dating from as early as the Han Dynasty (206

BC -220 AD), archeologists have discovered "trees" made of

bronze and having "leaves" shaped in the form of Chinese cash

coins. Based on the ancient legends, these objects have

been designated as "money trees" and are believed to be burial

objects used to guide the deceased to heaven and to provide

for their financial support while there.

In numerous tombs in

southwest China dating from as early as the Han Dynasty (206

BC -220 AD), archeologists have discovered "trees" made of

bronze and having "leaves" shaped in the form of Chinese cash

coins. Based on the ancient legends, these objects have

been designated as "money trees" and are believed to be burial

objects used to guide the deceased to heaven and to provide

for their financial support while there.The Chinese have always believed strongly in the efficacy of charms and amulets. Based on the legends and the common desire to be instantly and permanently wealthy, the Chinese have over the millennia created smaller examples of these "money trees" with the wish that they will bring good fortune to the owner while still alive.

A specimen of such a Chinese money tree, which happens to include replicas of very rare ancient coins, is discussed in detail below.

Coin Trees and Money Trees

First,

it is important to differentiate a "money tree" (yaoqianshu 摇钱树) from

what is commonly referred to as a "coin tree" (qianshu 钱树).

First,

it is important to differentiate a "money tree" (yaoqianshu 摇钱树) from

what is commonly referred to as a "coin tree" (qianshu 钱树).The term "coin tree" is usually associated with the traditional method of casting Chinese coins. Beginning in the Warring States period (475 -221 BC), Chinese coins were cast in molds which were made of clay, stone or bronze. By the time of the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907 AD), the coins were being made in sand molds.

Each mold would have a number of coin impressions so that many coins could be produced at a time. These coin impressions were connected by channels so that the molten bronze could be poured into the mold at one opening and then flow to all parts of the mold.

Once the bronze had cooled and hardened, the two halves of the mold were separated and the coins removed. However, since all the coins were connected by the channels through which the bronze had flowed, the bronze in the channels had hardened as well resulting in all the coins being connected together.

The metal object that came out of the mold actually looked like a small "tree". The main channel through which the bronze had flowed resembled the "trunk" of a tree. The smaller channels which ran from the main channel to each individual coin looked like "branches". The coins were the "leaves".

This is what is commonly referred to by Chinese numismatists as a "coin tree" and a very nice example, which is in the collection of The British Museum, is displayed at the left.

It appears that in China at least, the adage that "money does not grow on trees" is not quite correct.

The coins were then broken off of the "branches". This left a small metal stub, called a "sprue", on the edge of each coin where it had been attached to the "branch". The molding process would also leave a little excess metal on the edge of the coins. The sprues and excess metal needed to be filed off to improve the appearance of the coins.

The coins, which all had square holes in the center, were then stacked onto a square metal rod. The combination of a square rod threaded through the coins' square holes locked the coins from rotating on the rod and thereby made it easier for the worker to file off the sprue and excess metal on the edges of the coins.

Therefore, "coin trees" are different from the "money trees" being discussed here. However, because of the similarity in appearance, some scholars believe that in the very distant past the "coin tree" may have been the model for the "money tree".

Stories of the Origin of the Money Tree

There are several

legends relating to the origin of the Chinese money

tree.

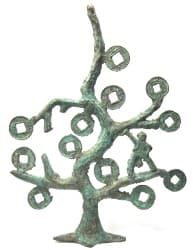

One story tells of an old white-haired man who gave a peasant a very special seed. The old man told the farmer to plant the seed and then to water it everyday. Not just any water could be used, however. The water had to be the beads of sweat from the peasant himself. Since the seed needed a lot of water in order to sprout, the farmer would need to provide a great deal of sweat everyday.

The old man then told the peasant that once the seed had sprouted, it would need to be continually watered. But not just any "water" could be used. The sprout would need to be watered with drops of blood from the farmer himself.

The peasant did as he was instructed and the resulting plant grew up to be a "money tree". The peasant found that by shaking the tree, coins would fall to the ground. The peasant became rich and, because new coins grew back to replace the coins that had fallen, the tree became a source of perpetual wealth.

While the story provides a magical origin for the money tree, the implied meaning is that a person actually becomes rich through hard work and relying on one's own sweat and blood.

A more literary source for the origin of the money tree has to do with the identical pronunciation of the Chinese word for "bronze" (tong 铜) and the Chinese word for the paulownia tree (tong 桐), also known as the phoenix tree or tung tree. The leaves of this tree are said to resemble Chinese coins. The leaves turn yellow in the autumn, and when the wind blows, they look like bronze or gold coins falling from the tree.

One story tells of an old white-haired man who gave a peasant a very special seed. The old man told the farmer to plant the seed and then to water it everyday. Not just any water could be used, however. The water had to be the beads of sweat from the peasant himself. Since the seed needed a lot of water in order to sprout, the farmer would need to provide a great deal of sweat everyday.

The old man then told the peasant that once the seed had sprouted, it would need to be continually watered. But not just any "water" could be used. The sprout would need to be watered with drops of blood from the farmer himself.

The peasant did as he was instructed and the resulting plant grew up to be a "money tree". The peasant found that by shaking the tree, coins would fall to the ground. The peasant became rich and, because new coins grew back to replace the coins that had fallen, the tree became a source of perpetual wealth.

While the story provides a magical origin for the money tree, the implied meaning is that a person actually becomes rich through hard work and relying on one's own sweat and blood.

A more literary source for the origin of the money tree has to do with the identical pronunciation of the Chinese word for "bronze" (tong 铜) and the Chinese word for the paulownia tree (tong 桐), also known as the phoenix tree or tung tree. The leaves of this tree are said to resemble Chinese coins. The leaves turn yellow in the autumn, and when the wind blows, they look like bronze or gold coins falling from the tree.

Historical Records and Archeological Discoveries

Chinese scholars believe that

the first historical mention of a "money tree" comes from the

"Records of the Three Kingdoms" (san guo zhi 三国志), written

by Chen Shou (陈寿) in the 3rd century AD, which

documents

the turbulent history of the ancient Chinese states of Wei

(魏), Shu Han (蜀汉) and Wu (吴) during the period 189 - 280 AD.

One

day, Bing Yuan (邴原) discovered a string of cash coins

on the ground as he was walking down the road. Unable to

find the owner of the lost money, he hung the string of coins

on a nearby tree. Other travelers on the road soon

noticed the coins hanging on the tree and, believing that it

must be a holy tree, hung additional coins on the tree with

the wish that it will bring them more wealth and good fortune

in the future.

One

day, Bing Yuan (邴原) discovered a string of cash coins

on the ground as he was walking down the road. Unable to

find the owner of the lost money, he hung the string of coins

on a nearby tree. Other travelers on the road soon

noticed the coins hanging on the tree and, believing that it

must be a holy tree, hung additional coins on the tree with

the wish that it will bring them more wealth and good fortune

in the future.

By placing strings of coins on the tree, people were following the ancient Chinese practice of making offerings and sacrifices with the hope that such actions would result in greater benefit in the future.

The concept of the "money tree", however, is actually rooted much earlier in Chinese history. During the excavation of a number of Han Dynasty (206 BC -220 AD) tombs, large and very ornate "money trees" have been discovered.

Many of these money trees have been unearthed in areas of Sichuan where the Wudoumi Dao ("Five Pecks of Rice") Daoist religious sect established by Zhang Daoling flourished.

Probably the most famous example is the 198 cm tall "money tree" unearthed at Eastern Han Tomb No. 2 in Hejiashan Village in Sichuan Province. This money tree has a pottery foundation with the tree cast in bronze. The money tree is decorated with strings of coins, as well as bronze dragons, phoenixes, elephants, deer, dogs, etc.

A Money Tree with Ancient Chinese Coins

One

day, Bing Yuan (邴原) discovered a string of cash coins

on the ground as he was walking down the road. Unable to

find the owner of the lost money, he hung the string of coins

on a nearby tree. Other travelers on the road soon

noticed the coins hanging on the tree and, believing that it

must be a holy tree, hung additional coins on the tree with

the wish that it will bring them more wealth and good fortune

in the future.

One

day, Bing Yuan (邴原) discovered a string of cash coins

on the ground as he was walking down the road. Unable to

find the owner of the lost money, he hung the string of coins

on a nearby tree. Other travelers on the road soon

noticed the coins hanging on the tree and, believing that it

must be a holy tree, hung additional coins on the tree with

the wish that it will bring them more wealth and good fortune

in the future.By placing strings of coins on the tree, people were following the ancient Chinese practice of making offerings and sacrifices with the hope that such actions would result in greater benefit in the future.

The concept of the "money tree", however, is actually rooted much earlier in Chinese history. During the excavation of a number of Han Dynasty (206 BC -220 AD) tombs, large and very ornate "money trees" have been discovered.

Many of these money trees have been unearthed in areas of Sichuan where the Wudoumi Dao ("Five Pecks of Rice") Daoist religious sect established by Zhang Daoling flourished.

Probably the most famous example is the 198 cm tall "money tree" unearthed at Eastern Han Tomb No. 2 in Hejiashan Village in Sichuan Province. This money tree has a pottery foundation with the tree cast in bronze. The money tree is decorated with strings of coins, as well as bronze dragons, phoenixes, elephants, deer, dogs, etc.

A Money Tree with Ancient Chinese Coins

Displayed at the left

is a much smaller and modest example of a Chinese money tree.

Displayed at the left

is a much smaller and modest example of a Chinese money tree.Unlike the exquisite money trees found in the Han Dynasty tombs, this bronze specimen does not have a separate pottery base.

Some money trees have auspicious symbols, such as bats, or images of immortals such as the Queen Mother of the West (xiwangmu 西 王母). This money tree does not have any such symbols.

However, the outstanding characteristic of this particular money tree is that the "leaves" on the branches are all replicas of rare ancient Chinese coins which predate the time this money tree was created.

The coins of ancient China are typically round with a square hole and are generally referred to as "cash" coins.

There are twelve such coins on this tree.

All of the "coins" have inscriptions which are identical to real coins. The inscriptions are also written in exactly the same calligraphic style as authentic coins.

These coins are identified and discussed in detail in the section below.

As can be seen, a man is standing on one of the lower branches with his right arm outstretched and his left hand on his hip. He is holding onto another branch and, presumably, shaking it in order to cause the coins to fall to the ground for him to then gather.

It is popularly believed that new coins grow on the branches to replace those that have fallen. The tree, therefore, can provide an inexhaustible supply of money.

This solid bronze money tree is approximately 18 cm in height and 13.5 cm in width.

Coins of the Money Tree

All the money trees found

in ancient tombs have replica Chinese cash coins, which

are round with a square hole in the center, attached to

their branches. Many times these coins have no

inscriptions or legends. If there is an inscription,

however, it is usually that of a real coin from the same

historical period in which the money tree was created.

Many money trees found to

date have come from Han Dynasty tombs and the replica

"coins" on the branches have the inscription wu zhu (五铢). This was the

inscription of a very common coin first cast at the

beginning of the Han Dynasty. Wu zhu coins

continued to be produced for over 700 years. (The wu zhu coin is

discussed in great detail at Emergence of Chinese

Charms.)

Many money trees found to

date have come from Han Dynasty tombs and the replica

"coins" on the branches have the inscription wu zhu (五铢). This was the

inscription of a very common coin first cast at the

beginning of the Han Dynasty. Wu zhu coins

continued to be produced for over 700 years. (The wu zhu coin is

discussed in great detail at Emergence of Chinese

Charms.)As mentioned above, all the coins on the money tree being discussed here are replicas of real, identifiable ancient Chinese coins.

There are a total of 12 coins and 4 varieties on this money tree.

For example, the coin displayed at the left has the inscription ding ping yi bai (定平一百). The ding ping yi bai coin was cast and used in the Kingdom of Shu Han during the years 221-265 AD. The Kingdom of Shu is one of the Three Kingdoms whose history is recorded in the "Records of the Three Kingdoms" mentioned above.

The leader of the Kingdom of Shu Han was Liu Bei (刘备) who is well known to all Chinese as one of the heroes of the famous 14th Century novel "Romance of the Three Kingdoms" (san guo yan yi 三国演义) written by Luo Guanzhong.

This is another "coin" on the money tree.

The inscription, written in seal script, is read right to left as liang zhu (两铢).

The liang zhu was cast in the year 465 AD during the Southern Dynasties by Emperor Qianfei of Liu Song.

Very few authentic liang zhu coins are known to exist and they are, therefore, very rare.

This is an even rarer "coin" cast during the same time (465 AD) and place as the above coin.

The inscription, also written in seal script and read right to left, is yong guang (永光).

Emperor Qianfei of Liu Song used the reign title "Yong Guang" for only a few months so real yong guang coins are extremely rare.

The final example of a "coin" from this money tree is actually much older than any of the others.

The inscription reads right to left as yi hua (益化).

This coin was cast during the Warring States Period (475 -221 BC) of the Zhou Dynasty.

It was cast and circulated in the State of Qi during the years 300 - 220 BC.

Return to Ancient Chinese Charms and Coins