Beginning in very ancient times, the Chinese included money among the objects buried with the deceased.

This burial money was referred to as yi qian (瘗钱), meaning “buried money”, or ming qian (冥钱), meaning “dark money”.

The money was to be used by the deceased in the afterlife to make life more comfortable. It was also offered as a “bribe” to Yan Wang (阎王 or yanluowang 阎罗王), the judge of the underworld, to encourage him to act quickly and favorably in regard to the spirit.

Ancient China had a number of interesting forms of money.

Cowrie shells (贝币) were one of the first forms of money that circulated extensively.

Graves evacuated from the Shang Dynasty (商朝 c. 1600 BC – 1046 BC) sometimes include thousands of cowrie shells. As an example, the Tomb of Fu Hao (妇好墓), dating from about 1200 BC, was found to contain 6,900 cowry shells.

Because the quantity of natural cowries were limited and could not meet the demand, bronze versions of the cowrie shell were cast and circulated as money.

During the Warring States period (战国时代 475 BC – 221 BC), other metal forms of money appeared. These early “coins” took on various shapes and included spade (bubi 布币), knife (daobi 刀币), ring-shaped coin (huan qian 环钱), ant nose (yibiqian 蚁鼻钱) and banliang (“half-tael” 半两).

These forms of money were also buried as funerary objects.

Unfortunately, the custom of burying money in tombs attracted the attention of grave robbers who throughout the ages have dug up graves in order to steal buried money and other valuable artifacts.

Having the grave of a relative desecrated in such a manner was extremely unsettling to the living relatives. The spirit of the deceased was disturbed and the money meant to ensure his comfort in the afterlife was gone.

To minimize the chances that a tomb would be disturbed, a change took place involving burial money. Instead of real money, imitation money was sometimes used.

This imitation money resembled real money but instead of being made of bronze, silver or gold, it was made of hardened clay.

These imitation coins are known as “clay money” (ni qian 泥钱) or “earthenware money” (tao tu bi 陶土币).

According to “Han Material Culture” by Sophia-Karin Psarras, any representation of currency was acceptable as legal tender in the afterlife. Therefore, surrogate forms of money made of clay could be used in lieu of real bronze, silver or gold money.

Since clay money had no value in the world of the living, it was believed that grave robbers would leave the deceased to rest in peace.

The use of surrogate currency was used by both the rich and poor alike since even families of modest means could afford to buy the imitation coins to bury with their relatives.

The wealthy who buried real money in tombs would often also include coins made of clay.

At the left can be seen cowries made of clay that were produced specifically to be buried in graves.

These particular specimens are unusually well-made.

The primary form of money that circulated during the Qin Dynasty (秦朝 221 BC – 206 BC), as well as the early Western Han Dynasty (西汉 206 BC – 24 AD), was the banliang (半两) coin made of bronze.

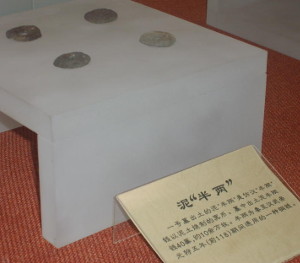

At the left are several clay banliang coins (泥半两) that were excavated from Tomb No.1 at Mawangdui and are seen here at an exhibit held at the Tianjin Museum.

Mawangdui (马王堆) is a major archaeological site located at Changsha (长沙), Hunan Province that includes three Western Han Dynasty tombs.

Tomb No. 1 is the resting place of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui 辛追).

Lady Dai’s tomb was one of China’s most important archaeological discoveries. As an example, more than 100,000 clay banliang coins were recovered from her tomb.

Beginning in 118 BC of the Western Han Dynasty (西汉) and continuing for more than 700 years, the major form of currency was the bronze wuzhu (五铢) coin.

These coins are commonly referred to as “cash coins”.

Clay versions of wuzhu coins (泥五铢) also exist and are frequently found in Han Dynasty graves.

As an example, a Han Dynasty tomb located near Shanghai’s fu quan shan (福泉山) contained several hundred clay wuzhu coins.

Examples of clay wuzhu coins can be seen in the image above.

The wuzhu coin, which is round with a square hole in the center, had a special significance in reference to the afterlife.

For the deceased ascending to the heavens, the wuzhu coin served as a cosmic map of the universe reflecting the Chinese view that the earth is square and the heavens are round.

In addition, the “zhu” in wuzhu can refer to the trunk of the 300 li tall fusang (扶桑) tree which is an auspicious symbol that guides the dead on the journey to the heavens and immortality, according to Susan Erickson in her article “Money Trees of the Eastern Han Dynasty”.

(For more information about money trees discovered in Han Dynasty tombs please see “Chinese Money Trees“.)

The wuzhu coins played a more down-to-earth role as well. The Chinese view of the afterlife gradually evolved so that the spirit world was seen to be similar to the earthly world. The money in the tombs could therefore be used by the deceased to pay taxes to the otherworldly government.

Clay versions of coins from later dynasties have also been unearthed in tombs.

For example, a Han Dynasty tomb in Henan (南阳英庄) contained more than 20 specimens of the Xin Dynasty (9 – 23) da quan wu shi (大泉五十) coin.

At the left is an example of a clay da quan wu shi coin.

Also, clay versions of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) kai yuan tong bao (开元通宝) coin have been unearthed in Tang and Song Dynasty tombs.

A clay specimen of a kai yuan tong bao (泥开元通宝) coin is shown at the left.

As an aside, during the Tang Dynasty there was an autonomous region in what is now Hebei that was under the control of a warlord named Liu Rengong (刘仁恭). He minted clay coins and iron coins, and then forced the people to trade in their bronze coins for these coins. This is a rare case where clay coins were officially minted for circulation and not for funeral use. Unfortunately, no specimens of these clay coins are known to exist.

At the left are examples of clay coins discovered in a tomb located in Shanxi. The tomb dates to the time of the Song (宋朝 960-1279) and Jin (金朝 1115-1234) dynasties.

The coin at the far right, for example, is a clay version of the chong ni zhong bao (崇宁重宝) coin written in Li script (“clerical script” 隶书) and minted during the years 1102-1106 of the reign of Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Shown at the left are rare examples of clay coins unearthed from Liao Dynasty ruins.

These clay coins have different inscriptions.

The inscription on the clay coin at the top left, for example, is tian chao wan shun (天朝万顺). Authentic Liao coins with the inscription tian chao wan shun are extremely rare and even clay burial versions are not often seen.

Clay burial coins with inscriptions of other very rare Liao coins were also discovered in the foundation of a Liao Dynasty pagoda.

Examples of these coins can be seen at the left.

The clay Liao coins included bao ning tong bao (保宁通宝), seen at the top left, and da kang tong bao (大康通宝) , seen at the bottom left.

Also discovered were a clay version of the da ding tong bao (大定通宝) coin from the Jin Dynasty which is shown at the top right.

Clay coins for burial use were being “minted” even as late as the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

At the left is a clay version of a qian long tong bao (乾隆通宝) coin.

Coins with this inscription were cast during the years 1736-1795 of the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

In addition to “low currency” (下币) money consisting of bronze coins such as the banliang and wuzhu coins that commonly circulated during the Qin and Han dynasties, there was also a “high currency” (上币) form of money that made its appearance during the Warring States period.

This money was made of gold and was used as currency as well as for sacrificial offerings, rewards, fines, etc.

Kings, nobility and the wealthy were frequently buried with this type of gold money in their tombs.

An example of the gold money that circulated in the State of Chu during the Warring States period may be seen at the left.

This money is known as yuan jin (爰金) and consists of small square gold cubes connected together in a form best described as a slab, plate or sheet. Individual squares could be broken off and spent as needed.

The yuan (爰) was a unit of weight and jin (金) means “gold”.

Each of the gold squares was also inscribed with Chinese characters. For this reason, these “coins” are also known as yin zi jin (印子金), jin ban (金钣) or gui bi (龟币). They are sometimes referred to in English as “ying yuan”, “gold plates”, “seal gold”, or “gold cube money”.

Some have the characters ying yuan (郢爰). Ying (郢), which was situated in what is now Jingzhou (荆州) County in Hubei Province, was the capital of the State of Chu.

The other inscription found on these gold coins is chen yuan (陈爰). After the Qin army captured the capital city of Ying, the State of Chu moved their capital to Chen which was located in what is now Huaiyang (淮阳), Henan Province.

At the left are clay specimens of the State of Chu’s yuan jin gold money (泥”郢称”(楚国黄金货币)) that have been recovered from tombs.

These particular specimens were unearthed in Zhejiang Province which was part of the ancient State of Chu during the Warring States period.

More than 300 pieces of this clay replica gold currency were also recovered from Lady Dai’s tomb at Mawangdui.

As can be seen, the imitation money has the same overall shape as the real gold money but is made of clay.

Careful observation shows that the surface design on these imitation sheets of gold money resembles square pieces of cloth or fabric.

This design could not be adequately explained prior to the discovery of Lady Dai’s tomb.

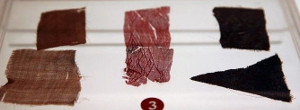

Silk was a valuable commodity in ancient times and bolts of silk could also function as a form of currency. Small “denominations” of this “money” were created by cutting the silk into small squares.

Several of these small square silk “coins” (丝织品做的冥币) were recovered from Lady Dai’s tomb at Mawangdui. This was the first time such silk squares functioning as a form of burial money had been discovered.

Shown above are several examples of this silk funerary money recovered from the tomb of Lady Dai that are now on display at the Hunan Provincial Museum.

It is believed that the State of Chu’s distinctive sheet form of gold money with the connected small squares may have been based on this very early type of silk money.

This would also explain why the clay imitation version of the gold money has a surface design that resembles fabric.

Lady Dai’s tomb actually contained a rich assortment of burial money.

Shown at the left is an exhibit case from the museum containing a variety of the imitation money from her tomb.

At the top left is a string of clay banliang coins.

At the lower left is the display of silk funerary money just discussed.

The lower middle of the display case has clay replicas of the State of Chu gold money.

At the lower right are clay imitation “gold pies” which will now be discussed.

During the Western Han Dynasty, a surprisingly large quantity of gold was in circulation with the estimate being more than one million jin (斤) equivalent to more than 248 tons.

One type of gold currency was about the size of a “cookie” and had the shape of a flattened half-sphere with the top convex and the bottom concave.

This form of gold money is variously referred to as a gold pie, gold cake, gold biscuit, gold bing ingot, gold button ingot, etc.

In Chinese it is known as jin bing (金饼).

According to this article, a gold pie has a high gold content of 97-99% and weighs about 248 grams (210 ~ 250 g.) which would be the equivalent of about 1 jin (斤) during the Han Dynasty.

The specimens shown above are on display at the Shaanxi History Museum in Xian. These gold pieces date from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 8 AD) and were excavated from a tomb in Xian.

As can be seen in the image here, gold pie coins sometimes have a Chinese character engraved on the bottom (right image).

Some of the characters can be identified such as 齐, 土, 长, 阮, 吉, 马, 租, 千, 金, 王, and “V“. Other characters will require further research.

Imitation specimens of these pie-shaped gold disks made of clay or earthenware (陶质”金饼”) are also being found in tombs dating to the Han Dynasty.

These cake-shaped funeral objects (mingqi 冥器) have not always been recognized in the West for what they really are.

For example, they have sometimes been mistakenly referred to as a “glazed plate of food”.

And just like the authentic gold pie money, some of the imitation clay cakes have inscriptions on the bottom.

As can be seen in the image at the left, this clay imitation gold pie has the Chinese characters feng nian tian (丰年田) inscribed on the bottom.

Feng nian (丰年) translates as a “good year” and tian (田) means a field or farm land.

The expression refers to a good year’s harvest and thus the value of this imitation gold “coin” is equal to a good year’s harvest from a plot of land.

There is no doubt as to the value of the clay specimen displayed at the left.

The inscription on the bottom reads zhi qian bai wan (直钱百万).

This translates as “worth one million cash coins”!

(Despite what the inscription says, a real gold pie was worth the equivalent of about 10,000 cash coins during the Han Dynasty.)

Nowadays, Chinese burial customs have changed somewhat. Real and imitation money is no longer buried with the dead. Instead, paper money known as joss paper (“gold paper” 金纸, 阴司纸), Hell money, Hell banknotes, and ghost money is burned instead.

While the custom has evolved, the basic concern for the financial well-being of the deceased remains the same.

Hell bank notes burned at funerals today have hyperinflated denominations of $10,000 to $5,000,000,000 or more.

While such large bank note denominations may appear excessive to us today, we have already seen that 2000 years ago there existed “clay” gold cake money valued at 1,000,000 cash coins.

Printed paper money involves two of the Four Great Inventions attributed to the Chinese, namely the inventions of papermaking and printing.

Cai Lun (蔡伦 50 – 121 AD), an official of the imperial court during the Han Dynasty, is recognized as the inventor of paper.

The Chinese were the first to use paper money which began during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 AD) but was not widely used until the beginning of the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279).

Historians can only speculate as to what that first paper money from the Tang Dynasty, known as “flying cash” or “flying money” (飞钱), may have looked like since no verified specimens are known to exist.

But, even as early as the Jin Dynasty (晋朝 265-420), joss was being made of gold foil.

And, it is possible that the first paper money may have been printed on yellow paper in order to give the appearance of the ancient gold sheet money dating back to the State of Chu.

There exist specimens of paper money which some collectors claim to be authentic “flying money” notes from the Tang Dynasty that are “printed on yellow paper using black ink”.

The current practice of burning joss and hell bank notes to provide money for the afterlife can be seen as the latest stage in the evolution of a custom that began in very ancient times with the burying of real and imitation money.

Leave a Reply