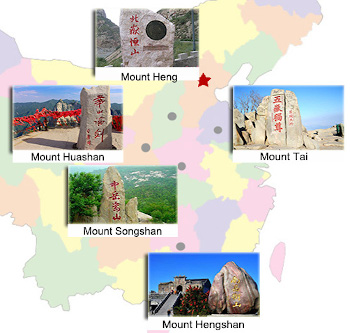

During the Eastern Jin dynasty (东晋 317-420), map-like charts began to be used as a guide in understanding the ultimate reality, i.e. the “true form” of things according to the Dao (Tao 道), during pilgrimages to China’s Five Great Mountains (五岳).

The “true form” is the original, formless, inner shape of the mountain, as part of the Dao, as opposed to its physical, visible, outer shape. Daoists (Taoists) believed that if one understood the true form (zhenxing 真形) of a thing or spirit, one could have control over it.

Daoists discovered sacred sites in the highest of places and, in particular, mountains and caves. They believed that caves were the very heart of a mountain and were a fountain of the vital life force known as qi (气). These mountainous areas had forests and streams where one could find medicinal plants and the ingredients for elixirs of life and pills of immortality.

Ge Hong1 (葛洪 283-343), a scholar and alchemist who lived during the Eastern Jin, warned: “Most of those who are ignorant of the proper method for entering mountains will meet with misfortune and mishap”.

Those accustomed to living in the plains and valleys were unfamiliar with mountainous topography, weather, and geology. They feared the tigers and other strange beasts as well as the local spirits and demons.

These charts (albums), which contained images that took the form of esoteric mountain landscapes seen from a bird’s-eye view, provided the guidance and protection needed during travels through the sacred areas.

One of the most famous of these charts was the “True Forms Chart of the Five Sacred Peaks” (五岳真形图), also known as “True Forms of the Five Marchmounts“, which was a book illustrating the “true form” of the Five Great Mountains (五岳) of China.

Ge Hong stated: “Having the Album of the True Forms of the Five Marchmounts in your home enables you to deflect violent assault and repulse those who wish to do you harm; they themselves will suffer the calamity they seek to visit upon you.”

Daoists later created talismans (charms) which displayed these charts. A talisman was more easily carried on the person and provided protection for seekers of the Dao as they journeyed into these mountainous areas.

Ge Hong wrote: “Others do not understand how to wear the divine talismans at their belt. Some do not obtain the methods to enter the mountains and let the mountain deities bring calamities to them. Goblins and demons will put them to the test, wild animals will wound them, poisons from pools will hit them, and snakes will bite them. There will be not one but many prospects of death.”

Unfortunately, only scriptures that refer to the “True Form Chart of the Five Sacred Peaks” still exist. The original text is no longer extant.

Fortunately, the talismans still exist because they continued to be cast and carried during the centuries that followed. The specimen discussed below dates to the Qing dynasty (清朝 1644-1912).

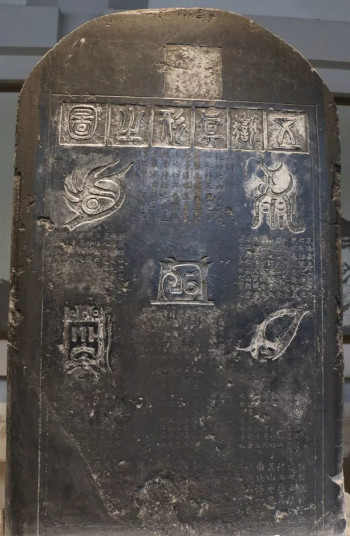

Shown at the left is the obverse side of a Daoist plaque (pendant) charm which is an example of a Daoist talisman (道教符箓).

A talisman is a charm that includes Daoist magic writing (fulu 符箓) which are special written characters that give orders to deities, spirits, demons, etc.

At the top of the charm is a medallion with the four-character Chinese inscription chi guo bai gu (赤郭白姑).

“Chi Guo” (赤郭) and “Bai Gu” were two mythical beings who provided protection from demons and were described as “ghost-eaters”.

Francois Thierry, an expert in East Asian currency, describes Chi Guo (“Lord Red”) as a supernatural giant, originally from southeastern China, who wore a red garment and had a red serpent wrapped around his neck. Lord Red was capable of swallowing 800 demons in the morning and 300 or 500 at night.2

Bai Gu was a mythical maiden also known for devouring evil spirits.

Any charm carrying the names of these two ghost-eaters would provide protection to those seeking the Dao in sacred summit areas.

The bottom portion of the charm is square with two small characters and one large character.

The two small Chinese characters at the top are 勅令 (chi ling) which translates as “edict”. The edict is expressed by the large character directly below.

The large character is not a Chinese character but rather Daoist magic writing, known as fulu (符箓) or lingfu (灵符). This character with its secret “edict” is what makes the charm a Daoist talisman.

Only Daoist priests know the exact meaning of magic writing but this character is believed to protect against disasters and to bring blessings.

To the left and right of the magic writing can be seen a curly grass pattern (唐草纹) which became popular during the Tang dynasty (唐朝 618-907).

Shown at the left is the reverse side of the charm.

The four-character inscription at the top reads lin lin guai guai (林林夬夬). Lin translates as “forest” and guai refers to the 43rd of the 64 hexagrams (六十四卦) in the Book of Changes (Yi Jing 易经).

The 43rd hexagram guai (夬) has the meaning “to respond strongly against opposing forces”.

This charm protects a Daoist from demons and savage beasts encountered in mountainous forests.

The lower square portion of the charm contains nine symbols. Some of these are Chinese characters and others are the “true form” maps of the five great mountains.

At the 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions are Chinese seal script (篆书) characters. Reading (top, bottom, right, left), they are wu yue zhen xing (五岳真形) which translates as the “true form of the five peaks”.

The other five special-shaped symbols are the “charts” (‘true form’ maps) of each of the five sacred mountains.

According to legend, Taishang Daojun (“Supreme Lord Tai Shang”, “Grand Lord of the Dao” 太上道君) passed these charts to the people to be used to prevent disasters and bring good fortune.

These symbols give a map-like representation of the mountains. As an example, the Japanese geographer Takuji Ogawa (小川琢治 1870-1941) believed that the “true form” map of Mount Tai was very similar to its topographic map.

The ancient Chinese had a strong belief in the number five (5) which originated with the Five Elements (wuxing 五行 metal, wood, water, fire, earth) also known as the Five Phases (五行).

The primal concept of the number five may have had its roots in a mathematical system based on five (one hand of five fingers) as opposed to a base ten (two hands with ten fingers).

Much of the Daoist worldview could be ordered into fives.

For example, there are the five great mountains and each is associated with one of the five directions (五方 north, south, east, west, center), five mythical animals (Four Auspicious Beasts (四象) and the Yellow Dragon), five colors (五色 yellow, red, green, black, white), and five emperors (Five Yue Emperors) (五岳大帝).

The five great mountains (五岳) and these associations are described below.3

Mount Tai (Taishan 泰山) in East China’s Shandong (山东) province has been the “abode of the immortals” (xian 仙) since ancient times and is the “East Peak” (东岳) of the Five Sacred Peaks. It is the holiest mountain in Daoism. For more than 3,000 years, Daoist pilgrims have journeyed to its Jade Emperor Peak (玉皇顶). The stone stele (碑), shown at the beginning of this article, is located at the Dai Temple (岱庙) on Mount Taishan.

Mount Tai is identified with the Wood (木) Element and the Azure Dragon (青龙). Azure is green-blue which is the color of the eastern fertile plains and the ocean.

The emperor of this peak is the “Holy Emperor Tian Qiren of Mount Taishan in Dongyue” (Grand Emperor of Mount Tai) (东岳泰山天齐仁圣大帝).

Mount Heng (Hengshan 衡山) in Hunan (湖南) province is the South Peak (南岳). At the foot of the mountain is the Grand Temple of Mount Heng (南岳大庙) which is the largest temple in south China. The temple contains an Imperial Tablet with an inscription written by the Kangxi Emperor stating “Mount Heng is the giant pillar in the south … and is also called Mount Longevity”.

Mount Heng is associated with the Fire (火) Element and the Vermilion Bird (朱雀). Vermilion is a reddish color which describes the red soils of the Sichuan (四川) and Yunnan (云南) provinces.

The emperor of this peak is the “Holy Emperor Si Tianzhao of Mount Hengshan in Nanyue” (Holy Emperor of Mount Heng 南岳圣帝) (南岳衡山司天昭圣大帝).

Mount Heng (Hengshan 恒山) in Shanxi (山西) province is the “North Peak (北岳). Mount Heng was the center of Quanzhen Daoism (全真道) and is where Yin Zhiping made pills of immortality.

Near Mount Heng is the famous Hanging Temple (悬空寺), built into a cliff 246 feet above ground, with a history of more than 1,500 years.

Mount Heng is associated with the Water (水) Element and Xuanwu (玄武) who is the “Mysterious Warrior” or Black Tortoise (龟蛇).

The emperor of this peak is the “Holy Emperor An Tianxuan of Mount Hengshan in Beiyue” (北岳恒山安天玄圣大帝).

Mount Hua (Huashan 华山) in Shaanxi (陕西) province is the West Peak (西岳). The five peaks of Mount Hua resemble a five-petaled flower explaining its common name as the “Flowery Mountain”. Mount Hua is considered the cradle of Chinese civilization and the “hua” in its name is also the origin of the Chinese name for China which is zhong hua (中华).

Mount Hua is associated with the Metal (金) Element and the White Tiger (白虎). White describes the snows of Tibet.

The emperor of this peak is the “Holy Emperor Jin Tianyuan of Mount Huashan in Xiyue” (西岳大帝) (西岳华山金天愿圣大帝).

Mount Song (Songshan 嵩山) in Henan (河南) province is the Center Peak (中岳) and where the Shaolin Temple (少林寺) is located.

Mount Song is associated with the the Earth (土) Element and the Yellow Dragon (黄龙). The loess soils of the Yellow River are yellow.

The emperor of this peak is the “Holy Emperor Zhong Tianchong of Mount Songshan in Zhongyue” (中岳嵩山中天崇圣大帝).

This Daoist charm, displaying ‘true form’ symbols, was created to guide and protect pilgrims traveling to the Five Great Mountains in their quest to discover the true reality known as the Dao.

If one were to ignore the advice to carry such a talisman, Ge Hong warned: “If someone enters the mountains possessing no magical arts, he will suffer harm”.

This charm is 86.6 mm long, 49 mm wide, and 3 mm thick. The weight is 67.1 grams. The charm sold at auction in 2018 for $3,900 (RMB 25,300).

1Ge Hong wrote the Baopuzi (抱朴子). An excerpt of this Taoist text is engraved at the bottom of the Stele at the Dai Temple on Mount Taishan.

2Francois Thierry, Amulettes de Chine (Paris: Bibliotheque nationale de France, 2008), 86.

3There are divergent opinions expressed in various Chinese references in regard to which chart symbol is associated with which mountain. In this article, I have associated the chart and mountain according to the inscriptions carved centuries ago on the Dai Temple stone stele at Mount Tai.