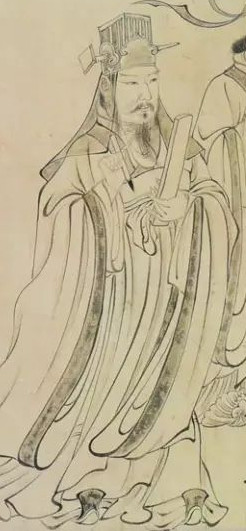

Bodhidharma (菩提达摩) was a Buddhist monk who came to China from Central Asia or the Indian subcontinent during the 5th or 6th centuries. Little is known about him but he is regarded as the founder of Chan Buddhism (禅) in China. Chan Buddhism eventually migrated to Japan where it further evolved into what is known as Zen.

Bodhidarma is highly recognized and respected in Japan where he is referred to as Daruma. As part of this adoration, the Japanese created a very popular doll in his honor.

These dolls are known as a daruma dolls. Daruma dolls are seen as symbols of perseverance, good luck and prosperity by the Japanese.

Daruma dolls are ubiquitous in Japan. Some are even used as “coin banks” (“piggy banks“) in which to save coins.

The daruma doll at the left is a most interesting and unusual example because Bodhidharma is shown holding a Chinese coin in his hands.

Bodhidharma has a striking appearance. He was not of Chinese ancestry and is described in ancient texts as being wide-eyed, heavy bearded and ill-tempered. Some texts even refer to him as the “Blue-eyed Barbarian”.

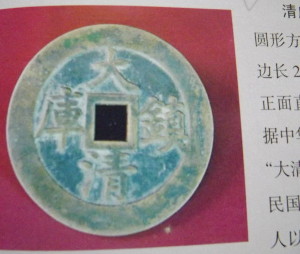

The Chinese coin he is holding is round with a square hole in the middle and is popularly known as a “cash coin”. Cash coins were used for more than 2,000 years in China and also became the model for the standard coinage of both Japan and Korea.

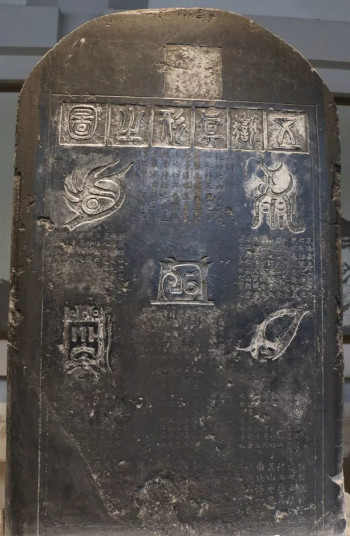

What is remarkable is that the daruma doll’s coin is so accurately detailed that it can be readily identified.

This type of coin is known as a “wu zhu” (五铢) and the inscription reads tai he wu zhu (太和五铢). Taihe (太和) is the era name of Emperor Xiaowen and wu zhu is the monetary denomination “five zhu“.

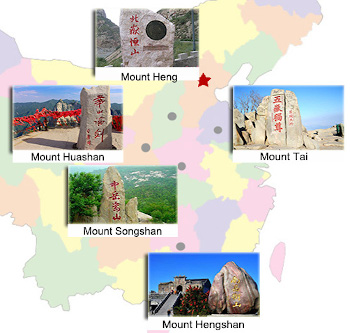

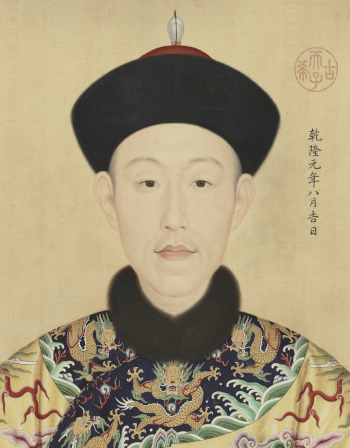

The tai he wu zhu coin was minted in 495 AD by Emperor Xiaowen (孝文帝 471-499) of the Northern Wei (北魏) in the capital city of Luoyang (洛阳).

This was the first coin issued during the Northern Wei. The inscription is a mixture of seal script (篆书) and clerical script (隶书) which comprises the classic Wei stelae style (魏碑体).

Tai he wu zhu coins tend to be fairly crudely made and vary in size and weight. Larger specimens are about 2.5 cm in diameter and weigh about 3 grams. Smaller specimens are about 2 cm and 2.3 grams.

These coins circulated only in the areas around Luoyang and never became the currency for the Northern Wei as a whole. For this reason, tai he wu zhu coins are relatively scarce.

It is important to note that Bodhidharma lived in the Luoyang area during the time that this coin circulated. Placing this specific coin in his hands is, therefore, historically accurate.

As mentioned above, Bodhidharma is usually portrayed as being “wide-eyed”. This alludes to a story concerning his nine years of staring at a cave wall while meditating. The legend goes that one day he fell asleep. In order to prevent this from ever happening again, he cut off his eyelids.

A Japanese legend states that after sitting and meditating in the cave for nine years his limbs atrophied. For this reason, daruma dolls do not have arms or legs. This particular daruma doll is a very rare exception. While it does not have arms or legs, it does have “hands” or, more accurately, a few fingers.

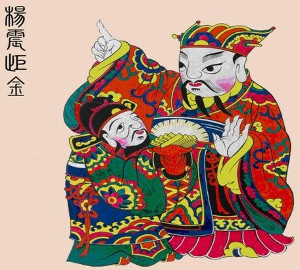

The Chinese have the expression jian qian yan kai (见钱眼开) which translates as “one’s eyes grow round with delight at the sight of money”. The expression first appeared in the famous Ming dynasty (明朝 1368-1644) novel Jin Ping Mei (金瓶梅) which is translated into English as The Golden Lotus or The Plum in the Golden Vase.

By a remarkable coincidence, there is a story dating from the Southern Song dynasty (南宋 1127-1279) that precisely illustrates this expression of a person going wide-eyed over the sight of a tai he wu zhu coin which is the same coin as in Bodhidharma’s hands.

The story takes place in the city of Suzhou (苏州) and concerns an elderly businessman with the surname Chai (柴) who literally loved money above everything else. He was extremely wealthy and was also extremely greedy and stingy.

One day he was out walking when he saw a group of children playing with some coins in the street. Because he loved money so much, he fixed his eyes on the coins. His eyes lit up when he noticed that some of the coins were tai he wu zhu. Tai he wu zhu coins were very valuable at this time and were much loved by the people.

Suddenly, one of the tai he wu zhu coins rolled under his feet. He quickly stepped on it to hide it from the children.

The children walked over and asked for the coin but the old man said, “I didn’t take your money.” One of the children replied, “It’s under your foot.”

The man quickly turned around and while his back was facing the children he picked up the coin. He then turned back around to face the children and said, “Look for yourselves, I don’t have any money under my foot.”

A child then pointed to the man’s hands and said, “It’s in your hand!”

The man spun around again and while his back was facing the children he put the coin in his mouth. He turned back to face the children and stretched out his hands to show there was no coin.

A child said, “It’s in your mouth!”

Knowing he had to hide the coin, he quickly swallowed it. He then opened his mouth wide so that the children could see there was no coin.

The man returned home with the coin stuck in his throat. He kept trying to cough it out but it would not budge. In less than a day, his throat became swollen and he had difficulty breathing.

His four sons wanted to call a doctor but the old man glared angrily at them and gestured with his hand to bring him a brush and ink. He then wrote, “For the sake of money, what would be the reason to spend money?”

By the third day, the man was close to death. His four sons came to his bed to discuss the funeral. The eldest son said, “You have worked hard all you life and should therefore have a coffin made of cypress.” The father just glared at his eldest son and shook his head indicating disapproval.

The Number 2 Son then said, “You have saved all your life and should have a coffin made of willow in order to save a lot of money.” The father again shook his head in disagreement.

The Number 3 Son then said, “After your death, we could wrap your body in the old reed mat on your bed and bury you. Would this satisfy you?” The father again shook his head.

The Number 4 Son was only 14 or 15 years of age but said, “After you die, we could chop your body into little pieces and fed the meat to your big yellow dog.”

The man smiled and vigorously nodded his head approvingly. He picked up his brush and breathlessly wrote the last words of his life:

After I die, chop me into pieces of meat and feed me to the dog.

But, don’t let him eat the tai he wu zhu coin!

The story serves as an example of a person being extremely wide-eyed in love with hoarding money and refusing to spend any of it even at the end of his life.

This daruma doll is carved from bone and has exquisite detail.

It is quite small as can be seen in the photo at the left.

Finally, we should not forget that Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who renounced the world, lived a very austere life in a cave, and spent a lifetime seeking true reality.

Over the centuries, Daruma’s legacy in Japan has evolved to the point where dolls are made in his image to serve as good luck charms and coin banks.

While the Japanese daruma dolls are very cute and symbolize perseverance, good luck and prosperity, the idea of associating the founder of Chan (Zen) Buddhism with something as secular and mundane as money is not consistent with his teachings.