In the early 1970’s, Buddhist monks digging in the courtyard of the Chengtian Temple (承天寺) in Quanzhou (泉州), Fujian Province in order to bury jars of a traditional Chinese medicine known as “golden juice” (jinzhi 金汁) made a startling discovery. They uncovered clay moulds (qianfan 钱范) used to cast ancient Chinese coins.

It was not until much later, in April of 2002, that archaeologists began a formal excavation. At a depth of about 3 meters they discovered more than a thousand clay mould fragments.

“Yong long tong bao” clay mould

The clay moulds were confirmed to have been used to cast the yong long tong bao (永隆通宝) iron coins made during the yong long reign (939-944 AD) of Wang Yanxi (王延曦) of the ancient Kingdom of Min (闽).

The actual location of the Kingdom of Min mint is not mentioned in the historical records. The large number of mould fragments discovered at the site therefore confirms that the mint was located in Quanzhou.

With the discovery of this coin-casting site, Quanzhou becomes the only known mint site from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (wudai shiguo 五代十国).

The reason for the large number of broken clay moulds has to do with the casting method employed at the time. A two-piece clay mould was made with a small hole in which the molten iron could be poured. Once the metal had hardened, the mould had to be broken to remove the coin. Each mold could therefore only be used to make one coin.

Yong long tong bao coins are very rare. It is estimated that only two specimens exist in China’s museums and that perhaps only about 100 specimens are in the hands of private Chinese coin collectors. The reason for the scarcity has to do with the short period of time (one year seven months) the coins were cast, the fact that iron rusts and deteriorates, the limited area in which the coins circulated, and the method of casting.

Besides iron, a very few specimens of the coin are known to exist made of bronze. An even smaller number are made of lead.

As can be seen from the images of the moulds above, the coins have the character min (闽) above the square hole on the reverse side and a “crescent” (月) below the hole. Some examples have a dot or “star” (星) to the right or left of the hole.

Iron was used to cast the coins because the Quanzhou area had ample supplies of iron and coal but lacked copper reserves. Even though the casting technique was the same as had been used since even much more ancient times, the technology had at least evolved to the point where Chinese inscriptions could be clearly cast. This means the molten iron had to be at a temperature of at least 1535°C.

Experts consider it particularly fortunate to have discovered these clay moulds. It is rare for such cultural objects to survive in climates that receive more than 1200 mm of rain per year as is the case with Quanzhou. This is believed to be one of the major reasons that no other sites which cast coins with clay moulds have been discovered this far south.

Display of Kingdom of Min clay mould fragments

The coin moulds are presently on display in a special exhibition room in Quanzhou.

As mentioned above, this discovery may not have ever been made if it were not for some Buddhist monks digging at the Chengtian Temple. The monks were digging a hole to bury “golden juice”.

“Golden juice” is a traditional Chinese medicine from the Quanzhou area. It is made by mixing together the feces of preadolescent boys, spring water and “red soil” (红土). The solution is then stored in a clay jar which is buried at a depth of about 3 meters. The jars are left in the ground for 30-40 years and then dug up.

“Golden juice” is taken orally and is considered to be particularly efficacious in the treatment of high fevers.

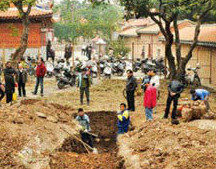

“Golden juice” being dug up at Cheng Tian Temple

The picture at the left shows about 40 jars of “golden juice” being dug up at Chengtian Temple after having been buried for some 38 years.

This was the last batch of “golden juice” made in 1973.

There is concern that interest in maintaining some of the local techniques of traditional Chinese medicine are dying off with the passing of the older generation.

In the past, jars of “golden juice” that were dug up would be replaced with new jars so that there would be a steady supply.

According to the article, people have lost interest in collecting and processing the excrement and, as a result, the jars are not being replaced.

The “golden juice” of Quanzhou may be destined to be another casualty in the rapid modernization of China.