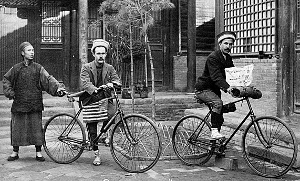

The two American cyclists reach north China in 1892. Few Chinese had ever seen a Westerner, much less a bicycle.

Two Americans decided to take a trip.

The year was 1890 and Thomas G. Allen Jr. and William L. Sachtleben had just graduated from my alma mater, Washington University in St. Louis.

The “ordinary” (“penny-farthing“) bicycle with the very large front wheel and very small back wheel was just beginning to be replaced by the new “safety” bicycle which had two small wheels with the rear wheel driven by chain and sprocket.

They decided to ride around-the-world on this new type of bicycle. They also purchased the newly introduced Kodak film camera to record their journey.

Their adventure was documented in a book they authored entitled “Across Asia on a Bicycle” and published in 1894.

During the three year journey, they experienced tremendous adventures.

Their travel across China began in 1892 in Kuldja which was the Russian name for the city of Yining in the far western region of Xinjiang.

Preparations for the grueling crossing to Peking were meticulous:

“Our work of preparation was principally a process of elimination. We now had to prepare for a forced march in case of necessity.

“Handle-bars and seat-posts were shortened to save weight…

“The cutting off of buttons and extra parts of our clothing, as well as shaving of our heads and faces, was also included…”

But a major challenge was how to carry money as these excerpts reveal:

“And now the money problem was the most perplexing of all.

“This alone,” said the Russian consul, “if nothing else, will defeat your plans.

“We thought we had sufficient money to carry us, or, rather, as much as we could carry…for the weight of the Chinese money necessary for a journey of over three thousand miles was, as the Russian consul thought, one of the greatest of our almost insurmountable obstacles.

William L. Sachtleben (right) with a Russian friend “loaded with enough Chinese ‘cash’ to pay for a meal at a Kuldja restaurant”.

“In the interior of China there is no coin except the chen or sapeks (referring to qian 钱 or “cash coins”), an alloy of copper and tin, in the form of a disk, having a hole in the center by which the coins may be strung together.

“The very recently coined liang, or tael (referring to Chinese minted ‘silver dollar’ coins), the Mexican piaster (referring to the Mexican silver coin) specially minted for the Chinese market, and the other foreign coins, have not yet penetrated from the coast. For six hundred miles over the border, however, we found … the Russian money… serviceable among the Tatar merchants, while the tenga (a silver coin of Russian Turkestan), or Kashgar silver-piece, was preferred by the natives even beyond the Gobi, being much handier than the larger or smaller bits of silver broken from the yamba bricks.

“All, however, would have to be weighed in the tinza, or small Chinese scales we carried with us, and on which were marked the fün, tchan, and liang of the monetary scale.

“But the value of these terms is reckoned in chen (Chinese cash coins), and changes with almost every district. This necessity for vigilance, together with the frequency of bad silver and loaded yambas, and the propensity of the Chinese to “knock down” on even the smallest purchase, tends to convert a traveler in China into a veritable Shylock.

“There being no banks or exchanges in the interior, we were obliged to purchase at Kuldja all the silver we would need for the entire journey of over three thousand miles.

“How much would it take?” was the question… That our calculations were close is proved by the fact that we reached Peking with silver in our pockets to the value of half a dollar.

“Our money now constituted the principal part of our luggage…

“Most of the silver was chopped up into small bits, and placed in the hollow tubing of the machines to conceal it from Chinese inquisitiveness, if not something worse.

“We are glad to say, however, that no attempt at robbery was ever discovered, although efforts at extortion were frequent, and sometimes…of a serious nature.”

The journey took three years and ended in New York in 1893. They became instant celebrities just as bicycling was beginning to become very popular.

Their extraordinary adventure, which I encourage you to read in its entirety, was described by one journalist as “the greatest journey since Marco Polo”.