A recent Chinese newspaper article describes how some valuable coins from a popular peasant uprising at the end of the Qing Dynasty were saved from being used as scrap iron for a backyard furnace during the Great Leap Forward campaign of 1958-1961.

The article entitled “Grandfather Saved Iron Coins from the Taiping Rebellion” was published in the May 5, 2011 edition of the “Chutian City News” (楚天都市报).

During the Great Leap Forward, Mao Zedong encouraged every commune and urban neighborhood to establish backyard steel furnaces in order to accelerate China’s economic development.

Since the village discussed in the article did not have the necessary iron ore to feed the furnace, every household was required to provide a specific quantity of “scrap iron”.

But the villagers also did not have “scrap iron” so they were forced to provide perfectly good iron utensils and tools in order to meet the requirement.

The “grandfather”, who happened to be one of the technicians in charge of the local furnace, discovered that someone had provided a string of 10-20 iron coins from the Taiping Rebellion as “scrap iron” for the furnace. He felt that it would be “a waste” to destroy the coins so he secretly hid them in his pocket and took them home.

Over the years, the coins were gradually passed down to various family members.

The Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) was a civil war which began in southern China. The leader Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全), who was convinced that he was the younger brother of Jesus, declared himself to be the “Heavenly King” (tian wang 天王) of “The Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace” (taiping tianguo 太平天国).

The rebellion would eventually spread through 15 provinces and include 30 million people before it was put down by government troops aided by French and British forces.

Most Taiping Rebellion coins were cast in bronze with only a very small number made in iron or lead. Gold and silver coins also exist but are extremely rare.

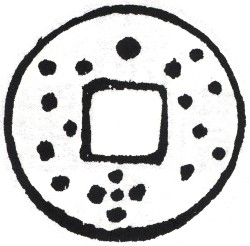

The coins have some interesting characteristics. For example, none of the coins bear a denomination. Also, the character guo (国) in the inscription, which means “kingdom”, is written with a wang (王) character inside the “square box” (kou 口) instead of the standard yu (玉) character.

The inscriptions on the coins can also vary. Obverse inscriptions include tian guo (天国), taiping tianguo (太平天国) and tianguo shengbao (天国聖寶). Reverse inscriptions can include shengbao (聖寶) and taiping (太平).

The iron coin shown in the article and displayed here has the obverse inscription “Heavenly Kingdom” (tianguo 天国) and the reverse inscription “Holy Coin” (shengbao 聖寶).

The coins have a diameter of 35 mm and weigh about 16.3 grams.

The Great Leap Forward proved to be an economic disaster for China with the “backyard furnaces” being just one example. Labor was diverted from the fields, the wood needed for the furnaces came from the doors and furniture of the peasants, the needed “scrap metal” consisted of perfectly good pots and pans, and the resulting pig iron was of such poor quality as to be useless.