Scientists have discovered a Ming Dynasty coin in Kenya that “proves China was trading with East Africa BEFORE Europeans arrived”, according to a recent newspaper article. The report, which was carried by newspapers around the world, claims that the coin provides evidence that the famous Chinese Admiral Zheng He reached East Africa years before the European explorers.

Ming Dynasty yongle tongbao coin discovered in East Africa

A joint expedition led by Chapurukha Kusimba of The Field Museum in Chicago, and Sloan Williams from the University of Illinois at Chicago, found the 600 year-old Ming Dynasty coin on the island of Manda which is located off of Kenya’s northern coast.

The Field Museum website provides a direct link to the newspaper article.

The coin, shown at the left, has the inscription yongle tongbao (永乐通宝) and was cast during the reign (1402-1424) of the Yongle Emperor, also known as Emperor Chengzu (成祖), of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Zheng He was a eunuch who became China’s most famous maritime explorer.

According to Dr. Kusimba, the curator of African Anthropology at The Field Museum, “Zheng He was, in many ways, the Christopher Columbus of China”.

During the period 1405-1433, Zheng He led seven major maritime expeditions across the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. He also sailed into the Persian Gulf and Red Sea. His sea travels took him as far west as the east coast of Africa.

Comparative size of the ships of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus

Zheng He’s trade missions must have presented a spectacular sight.

Some of the ships were very large. His fleet consisted of more than 200 ships including about 28,000 men.

These vessels departed Chinese ports carrying not only the yongle tongbao coins, but also silver, gold, silk and blue-and-white porcelain.

While the report emphasized that this coin “may ultimately prove (Zheng He) came to Kenya”, the significant role the yongle tongbao coins played as the international currency of the time was not addressed.

Surprisingly, the traditional Chinese “cash coin” with a square hole in the middle was not the major form of money during the Ming Dynasty.

In fact, the production of cash coins actually ceased in 1393.

Ming Dynasty China relied instead on paper money and silver as the primary forms of money.

The situation changed beginning in 1405 when the Yongle Emperor ordered Zheng He to set sail on the Western Seas in order to expand political, economic and cultural ties with the countries of Southeast and South Asia.

In 1408, the Yongle Emperor ordered that traditional cash coins again be produced. The coins were cast at mints in Beijing, Nanjing, Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian. The coins were to carry the inscription yongle tongbao.

It is important to note that the coins were not produced to circulate within the country since China continued to rely on paper money and silver as the dominant forms of currency. The coins were specifically made for use in foreign trade and to be bestowed as rewards.

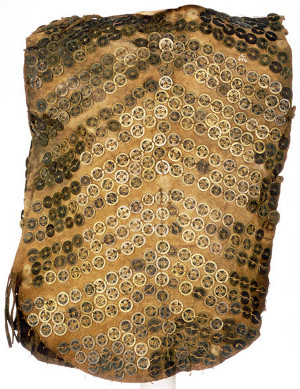

These coins were minted because many countries in the Orient liked to use the traditional Chinese cash coins as their circulating form of money. The areas included Indonesia, the Malay Peninsula, Singapore, Thailand, India and Sri Lanka. Even today, large quantities of Chinese cash coins are still being unearthed in these countries.

Korea and Vietnam also used Chinese cash coins for a very long period of time and these coins are still being unearthed in these countries with quantities sometimes being several tens of tons.

Japan imported large quantities of Ming Dynasty coins including both yongle tongbao and hongwu tongbao (洪武通宝) coins.

These coins even reached North America. A yongle tongbao coin was recently discovered in Canada’s Yukon Territory and the Canadian archaeologists believe it arrived during pre-gold rush trading.

Since the coins were primarily used only for foreign trade, very few yongle tongbao coins are found in archaeological digs within China’s borders. It is not uncommon for buried coin hoards dating from the Ming Dynasty to not include a single yongle tongbao coin.

On the other hand, coin hoards dating from the Ming era unearthed in neighboring countries frequently include yongle tongbao coins.

Such discoveries provide strong evidence that these coins were produced primarily for use in foreign trade.

Yongle tongbao coins tend to be extremely well made. They are well-cast with uniform size and weight and exhibit exquisite calligraphy.

The newspaper article, however, contains several puzzling statements.

For example, the coin is described as being made of “copper and silver”.

According to a research article entitled “An Investigation of the Using of Brass in Casting Coins in Ancient China” (我国古代黄铜铸钱考略) included in “A Collection of Chinese Numismatic Theses” (中国钱币论文集) published in 1992, an analysis of a number of yongle tongbao coins showed that they were composed of the following metals: copper (Cu) 63-90%, lead (Pb) 10-25%, tin (Sn) 6-9% and zinc (Zn) 0.04-0.18 %.

As can be seen, the coins have no silver content.

Another questionable statement in the newspaper article describes the coin as having “a square hole in the center so that it could be worn on a belt”.

The square hole allowed Chinese cash coins to be strung together to make them easier to carry. It also made it easier to file off excess metal from the rims during the manufacturing process.

Unless there is some pertinent information missing from the article, this coin was not minted so that it could be worn on a belt.

But despite all the hoopla accompanying the announcement of the discovery, the truth is that this was not the first time a yongle tongbao coin had been found in the area.

Yongle tongbao coin unearthed by Kenyan and Chinese archaeologists in Malindi in 2010

The BBC reported in 2010, more than two years earlier, that a yongle tongbao coin had been unearthed by a team of Kenyan and Chinese archaeologists at a village just north of Malindi on Kenya’s north coast.

In the BBC article Professor Qin Dashu of Peking University states that “these coins were carried only by envoys of the emperor, Chengzu (Yongle Emperor)”.

The discovery of the coin at Malindi was particularly intriguing because Chinese historical records mention that Zheng He brought back to China a giraffe from Malindi. The Chinese believed that the giraffe was the mythical Chinese qilin known in the West as the “Chinese unicorn”.

Nevertheless, the recent discovery in Kenya of a second yongle tongbao coin provides additional evidence that Zheng He and the Chinese were trading in this part of the world years before Vasco da Gama arrived in Malindi and Kenya in 1497-1498.

It is not by accident that both Chinese coins discovered in Kenya are yongle tongbao coins. The yongle tongbao coin was produced specifically for use in foreign trade and during the early 15th century served as the de facto “international currency” for much of the region.