Various forms of non-governmental currencies began to appear in the Changzhou (常州) area of Jiangsu Province (江苏省) during the early years (1939-1941) of the Japanese invasion and occupation of China (zhongguo kangri zhanzheng 中国抗日战争).

These currencies were issued by various stores and individuals and only circulated in a very limited area. They took the form of metal tokens, bamboo tallies, paper money, etc.

The necessity for such local currencies was due to the lack of small denomination coins and paper money issued by the government.

Other factors also played a role. It was very profitable for dealers to take old Chinese copper coins and convert them to coins for local circulation. Also, the local populace had very little confidence in the currencies issued by the Japanese-backed “puppet” government.

Local businesses also found it advantageous to issue these small denomination tokens in order to facilitate business transactions, establish prestige and promote the local economy.

Among the most interesting of these local currencies were those issued for circulation in the town of zhenglu qiao (郑陆桥) which translates as “Zheng Lu Bridge”.

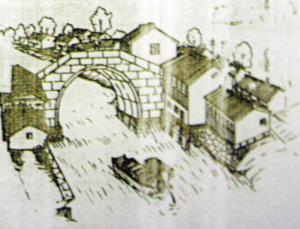

Zheng Lu Bridge illustrated in old book

The town was actually named after a bridge, shown here in an illustration from an old book, and the bridge’s construction was the result of a love story.

Prior to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), there was neither a town nor even a bridge in the area.

There was only a small street by the name of Zhenglu Street (郑陆街). Changzhou is the hub of a number of rivers, canals and lakes. At the time, a large number of people with the surname Zheng (郑) resided on one side of the river and people with the surname Lu (陆) dwelled on the opposite side. That is how the street got its name.

One day during the Longqing reign (隆庆 1567-1572) of the Ming Dynasty, a beautiful young woman from the Lu clan living in Dongshu Village (董墅村) happened to cross the river by ferry and was walking down Zhenglu Street when she noticed a handsome young man with a refined manner standing near the window on the second floor of his house reading poetry out loud. She glanced upwards, their eyes met, and she was immediately captivated by him.

When she returned home, she could “no longer think of food or sleep”.

As for the young man, he could no longer “smell the fragrance of flowers or read books”.

Her family immediately noticed the change in her behavior, and when asked the reason she confided her love for the young man.

The mother went to Zhenglu Street to find the object of her daughter’s affection. Several people were able to tell her the young man’s family name was Zheng. The young man was described as being generous, reliable and one who loved to read. She also discovered that the two families were very similar in regard to wealth and social status.

The two families arranged a meeting and it was decided that the two young people would marry in three months time which would be on the eve of the Spring Festival (春节).

But, in order to get to Dongshu Village from Zhenglu Street one needed to take a ferry to cross the river. For the sake of the wedding, it was decided that taking the ferry would be too dangerous. Also, it would not be convenient carrying all the wedding gifts on a ferry.

The two families therefore decided to use the three months time to build a wooden bridge to span the river. Since the families were well-off, the expense to build the bridge was not a problem.

The bridge was finished the day before the wedding and well-wishers were thus able to come and see the beautiful bride as she crossed the new bridge on her way to the wedding ceremony.

Zheng Lu Bridge token with heart symbol

To the local residents, the Zheng Lu Bridge also symbolized another famous “love” bridge. In Chinese mythology, two separated lovers known as the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl are allowed to meet once a year during the Qixi Festival (七夕节) by crossing a “Magpie Bridge” (鹊桥) which is a bridge composed of flying magpies that spans the stars.

An example of a Zheng Lu Bridge token displaying a “heart” symbolizing love is shown here. At the top is written “Zheng Lu Bridge” (鄭陸橋) and in the center of the heart is the denomination “five cents” (“five fen” 伍分). To the right and left of the heart is 臨時流通 which means “temporary circulation”.

The bridge quickly became very popular as a convenient way for people and goods to cross the river. Streets gradually were built in the area and stores, hotels and other businesses were established or moved to the area from Zhenglu Street.

However, as the years passed the wooden Zheng Lu Bridge deteriorated to the point that it had to be replaced with one made of stone.

The local people liked the story associated with the old bridge so much that they made sure that the name “Zheng Lu Bridge” was engraved in stone on the new bridge.

After several hundred years, the Zheng Lu Bridge was again rebuilt of stone in 1878.

In 1929, the area known as Zheng Lu Bridge officially became the “town” of Zheng Lu Bridge. In October of 1957, “Zheng Lu Bridge Town” was officially renamed “Zheng Lu Village”.

Zheng Lu Bridge token

As mentioned and illustrated above, various businesses found it advantageous to issue token forms of money during the period of the Japanese occupation.

Some of these tokens actually display images of the “Zheng Lu Bridge” as the theme.

At the left is an example of such a token. At the top of the token is the inscription zheng lu qiao liu tong (鄭陸橋流通) which translates as “Circulates in Zheng Lu Bridge”.

The two characters in the middle of the token state the denomination as “five fen” (“five cents” 伍分).

The lower half of the token displays the stone Zheng Lu Bridge with a boat passing underneath.

Reverse side of Zheng Lu Bridge token

The reverse side of these tokens usually displays the name of the person or business that issued the token.

The reverse side of the above token is shown at the left.

This particular token was issued by the Li Sanda Fabric Store (李三大布號). The serial number of the token is shown below the name.

Similar Zheng Lu Bridge tokens exist that were issued by other businesses and individuals.

Zheng Lu Bridge as it exists today

Unfortunately, in October 1971 the old stone Zheng Lu Bridge had to be torn down in order to dredge and enlarge the Beitang River (北塘河).

However, in September 1980 an arched bridge made of concrete was built near the original site as seen in the image at the left.

In remembrance of the love story that occurred some 400 years earlier, the new bridge is appropriately named “Zheng Lu Bridge”.